Content note: This piece includes discussion or imagery tied to sex, substance use, and erotic imagery. It may be activating for readers with addiction histories around sex, substances, or stigma. Please take care while reading.

I picked up some art today from Magpie’s First Friday exhibition. February’s theme was The Dark Side of Love. I had submitted a piece titled “Nothing Bad Happened.”

For March, the theme is HOOKED: An Exploration of Addiction.

As someone in recovery from chemsex addiction, I hesitated to submit something. The shadow does not disappear just because behavior changes. It shows up in memory, in intimacy, in fantasy.

Addiction has been described as a thinking disease. My instinct is to outrun the thoughts or distract myself. My therapist tells me to sit with them instead.

Relapse Fantasy came from doing exactly that.

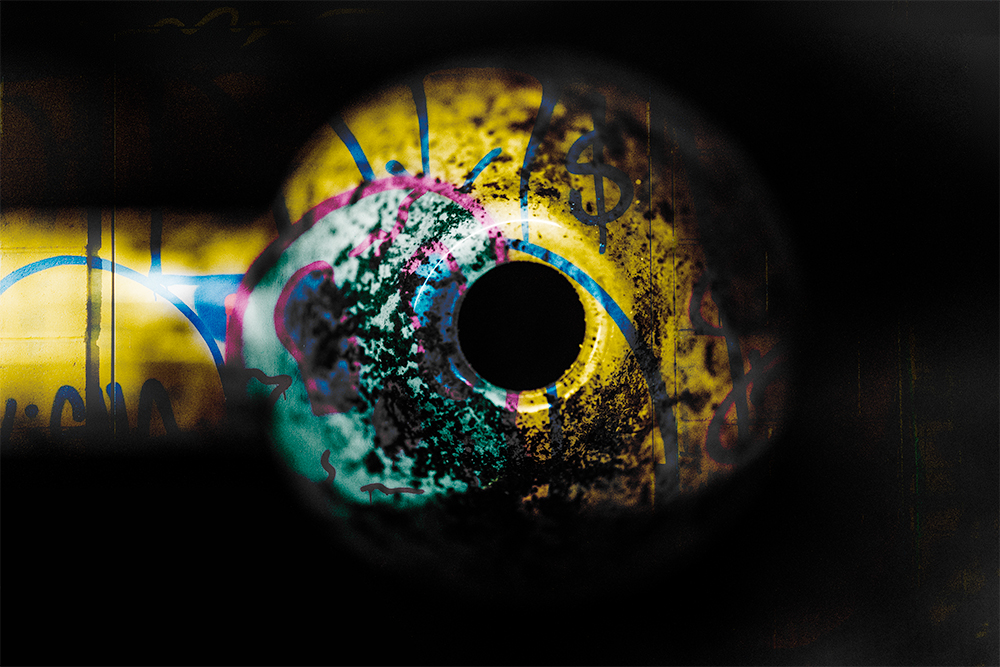

Relapse does not start with using. It starts in imagination. In a flicker of memory. In a sensory echo. Rather than pushing those thoughts away, I photographed them.

These images are not about returning to old behavior. They are about recognizing the moment before it begins. They are about interrupting the cycle in real time.

My work may not sell. That isn’t the measure. For me, creating it is part of staying accountable. I am in recovery, and this work is part of how I maintain it.

“I am being called to take care of myself in a new way.” ~ AB

Relapse Fantasy

Exhibition Statement

Artist Statement – Relapse Fantasy

Relapse doesn’t begin with action. It begins with a story I tell myself.

Chemsex addiction fuses sex and stimulant use in a way that rewires the brain’s reward and attachment systems. Dopamine begins to feel like intimacy. Intensity begins to feel like connection. The brain remembers that pairing long after behavior changes, and it can make the fantasy sound almost reasonable.

Relapse Fantasy explores that negotiation with the brain — the moment when pleasure tilts toward compulsion, when “just a taste” sounds logical, when repetition disguises itself as ritual and obsession passes for desire.

I’ve stood inside that logic.

I’m not documenting use. I’m documenting the sales pitch.

As someone navigating recovery in real time, I make this work to externalize the thought before it becomes behavior. The fantasy isn’t neutral. It’s persuasive. Naming it is how I interrupt it.

Chemsex is not only an individual struggle. It reflects how quickly intimacy and intensity become entangled in queer culture in ways we rarely name out loud.

If this work resonates uncomfortably, that’s okay. Discomfort can be information.

If this work resonates with your own experience, I encourage you to seek support. You do not have to navigate it alone. If you are struggling with addiction, support is available at 988 (https://988lifeline.org/) or local recovery services (Indianapolis resources).

Keep tellin’ the story,

Professor Peacock

Note: These are my thoughts and my story. I used AI to make helpful edits to my ramblings and online journaling, including some organization to be more blog-friendly. Images are photographed and manipulated by me.